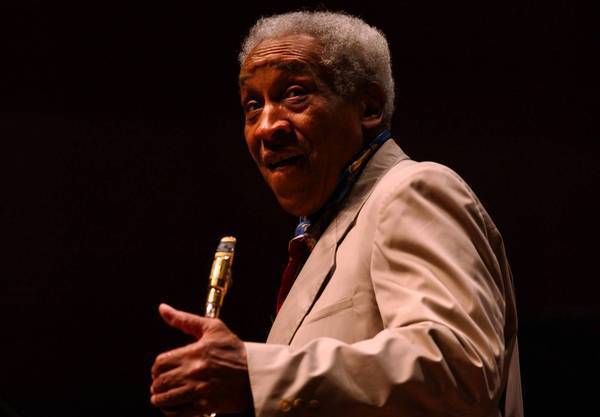

Von Freeman, Chicago's legendary jazz saxophonist has made his transition at the age of 88.

The tenor saxophonist came to the University of Chicago's Mandel Hall on Thursday, Feb. 24, 2011 to give a free performance with the Von Freeman Quartet and to discuss his life, career and music with Chicago Tribune jazz critic Howard Reich. In June 2011, the University of Chicago awarded Freeman the Rosenberger Medal, an honor established in 1917 by Mr. and Mrs. Jesse L. Rosenberger to "recognize achievement through research, in authorship, in invention, for discovery, for unusual public service or for anything deemed to be of great benefit to humanity."

Born in Chicago, IL., as a young child Freeman was exposed to jazz. His father, George, was a close friend of Louis Armstrong with Armstrong living at the Freeman house when he first arrived in Chicago. Freeman learned to play the saxophone as a child and at DuSable High School, where his band director was Walter Dyett. He began his professional career at age 16 in Horace Henderson's Orchestra. He was drafted into the Navy during World War II and played for a Navy band while in the service.

After his return to Chicago, where he remained for the duration of his career, he played with his brothers George Freeman on guitar and Bruz (Eldridge) Freeman (who died in 2006 aged 85 in Hawaii) on drums at the Pershing Hotel Ballroom. Various leading jazzmen such as Charlie Parker, Roy Eldridge and Dizzy Gillespie played there with the Freemans as the backing band. In the early 1950s, Von played in Sun Ra's band.

Von's first venture into the recording studio took place in 1954, backing a vocal group called The Maples for Al Benson's Blue Lake label. He appeared on Andrew Hill's second single on the Ping label in 1956, followed by some recording for Vee-Jay with Jimmy Witherspoon and Albert B. Smith in the late fifties, and a recorded appearance at a Charlie Parker tribute concert in 1970.

In 1972, Freeman first recorded under his own name, the album Doin' It Right Now with the support of Roland Kirk. His next effort was a marathon session in 1975 released over two albums by Nessa. Since then he lived, regularly performed, and recorded in Chicago. His recordings included three albums with his son, the tenor saxophonist Chico Freeman, and You Talkin' To Me with 22-year old saxophonist Frank Catalano, following their successful appearance at the Chicago Jazz Festival in 1999.

One of Von's singular contributions was his mentoring of countless younger musicians and his steadfast support of what he liked to call "hardcore jazz"(as he still did in a 2001 article in Downbeat.) Von's quartet played Monday nights throughout the 1970s and the mid-1980s at The Enterprise Lounge which closed when he toured Japan, and then Tuesdays at The Apartment Lounge. The quartet played a long set first, the vehicle that showcased Von's range from sensitively unwound ballads to intense improvisations that utilized his sometimes rough timbre and indefinite pitch to create a unique avant garde style of his own. His performances were also impressive verbal ones, as he served as an important figure that both helped African-American culture thrive on the South Side as well as invited the participation of European-Americans and others into the warmth of the community he and the rest of the Enterprise and Apartment created.

Freeman was considered a founder of the "Chicago School" of jazz tenor saxophonist along with Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin and Clifford Jordan. His music has been described as "wonderfully swinging and dramatic" featuring a "large rich sound". "Vonski," as he was known by his jazz fans, was selected to receive the nation's highest jazz honor, the NEA Jazz Masters award. Von transitioned in Chicago due to heart failure on 11 August 2012 at the age of 88.

Von Freeman was a critical favorite but never a big star. He merged elements of down-home blues, R&B honking and brazenly avant-garde techniques, and was a master of bebop.

|

August 17, 2012

Von Freeman was revered as a tenor saxophonist but was never a major star, worshiped by critics but perpetually strapped for cash. He seemed to purposely avoid commercial success. When trumpeter Miles Davis phoned Freeman in the 1950s looking for a replacement for John Coltrane, Freeman made a typical move — he never returned the call.

His refusal to leave his native Chicago during most of his career cost him incalculable fame and fortune but also enabled him to create a body of distinctive and innovative work. This year he received a Jazz Masters Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, regarded as the nation's highest jazz honor.

He had mentored countless younger jazz musicians, including his son, Chico Freeman, who became more famous than his father as a tenor saxophonist.

Freeman died Saturday of heart failure at Kindred Chicago Lakeshore care center, said another son, Mark. He was 88.

His relative obscurity was a blessing, according to Freeman. It enabled him to forge an unusual but instantly recognizable sound and to pursue off-center approaches to his music.

When his "weird ideas" were criticized, it didn't matter, Freeman told the Chicago Tribune in 1992: "I didn't have to worry about the money — I wasn't making" much. "I didn't have to worry about fame — I didn't have any. I was free."

He represented the quintessential jazz musician, forging a unique and influential musical voice. He staked out an exotic but alluring artistic territory, merging elements of down-home blues, R&B honking and brazenly avant-garde techniques. He was an utter master of bebop, the predominant jazz language of the 20th century.

"You hear one note, you know that's his sound," Fred Anderson, another noted Chicago tenor saxophonist, once said. "He took a lot from a whole lot of people and created Von Freeman."

He was born Earle Lavon Freeman on Oct. 3, 1923. His mother played the guitar, and his policeman father was an amateur jazz trombonist who brought jazz musicians home from the club where he moonlighted as a bouncer.

After 7-year-old Von pulled the arm off the family Victrola, bored holes in it and turned it into a crude horn, his father bought him a saxophone.

By age 12, Freeman was playing professionally. When he debuted at a nightclub, his mother sent along a note that read in part: "Don't let him drink, don't let him smoke, don't let him consort with those women…."

At Chicago's DuSable High School, Freeman studied under the venerated band director known as Captain Walter Dyett, who was training a new wave of jazz talent that included Nat King Cole and Dinah Washington.

In 1940, Freeman played with Horace Henderson's Chicago band before being drafted during World War II. He was soon performing with a Navy jazz band.

After the war, Freeman and his two jazz-playing brothers — guitarist George Freeman and drummer Eldridge "Bruz" Freeman — spent several years as the house band at Chicago's Pershing Hotel. Von also played with future free jazz pioneer Sun Ra in the late 1940s.

By then, Freeman was a fluid improviser, a brilliant technician and, as always, a singular voice with a focused intensity.

At 49 in 1972, Freeman cut his first record as bandleader, "Doin' It Right Now." Like other Freeman releases of the '70s and '80s — "Have No Fear" and "Serenade and Blues" — "Doin' It Right Now" captured the piquant quality of Freeman's tone and the majesty of his soliloquies yet failed to find a broad audience.

His only taste of major-label success came in 1982, when Columbia Records released the album "Fathers and Sons," featuring Ellis Marsalis with sons Wynton and Branford on Side A and Von and son Chico on Side B.

By the early 1980s, Freeman — who was nicknamed "the great Vonski" — was focusing purely on jazz and developing a cult following of fans who trekked to Chicago to hear the jazz giant once called "tragically under-recorded."

Freeman is survived by his brother George; his sons Mark and Chico; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Copyright © 2012, Los Angeles Times |